As I wrote earlier in my blog about the material reciprocity test under the Berne Convention, differing views have long existed on the copyright protection of works of applied art. The judgment of the District Court of Midden-Nederland of 12 November 2025 once again confirms this. Whereas the German Bundesgerichtshof (“BGH”) ruled earlier this year that the Birkenstock sandal does not meet the threshold for copyright protection, the court in Utrecht appears to take a different view. In this blog, I’ll discuss the court’s judgment.

Harmonised Copyright Work Concept?

Not only is there debate about whether and to what extent utilitarian objects can qualify for copyright protection; IP practitioners also disagree on whether the copyright concept of a “work” is harmonised at all.

In an interim judgment from July 2024, the same District Court of Midden-Nederland held that the concept of a copyright work is indeed harmonised within the European Union, but that such harmonisation is limited to the criteria for determining whether an object qualifies for copyright protection:

(1) the object must be identifiable with sufficient precision and objectivity, and

(2) it must be original as the author’s own intellectual creation.

However, the court emphasises that the application and assessment of this criterion in practice are not harmonised. Judges in different Member States must independently determine whether the requirements are met, based on the parties’ arguments and the specific facts and circumstances of the case.

The court even states explicitly that there is no inconsistency if the German court were to hold that no German copyright exists in the Birkenstock sandals, while a Dutch court were to hold that Dutch copyright does exist in the same sandals. According to the court, such a discrepancy is inherent in a system where national judges must make an independent assessment.

BGH Germany

Referring to Cofemel, the BGH acknowledges — like the District Court of Midden-Nederland — that the concept of a copyright work is harmonised and must be interpreted uniformly, but that the factual assessment of whether an object satisfies the criteria remains a task for national courts. The BGH upheld the judgment of the Oberlandesgericht Köln, which had previously held that Birkenstock sandals are not copyright-protected works of applied art under German copyright law.

Although the BGH recognises that the sandals have a consistent and recognisable appearance, and that various design choices were available, it considers that this design freedom was not exploited in a sufficiently creative way to rise clearly above the ordinary. In the BGH’s view, the design appears primarily aimed at creating a product that is healthy for the foot yet commercially viable, without involving an “artistic performance” that reflects the maker’s personality. Some argue that the BGH, by using this term, sets a higher bar for protection, whereas the BGH believes that “artistic performance” fits within the CJEU’s concept of “the author’s own intellectual creation”.

District Court Midden-Nederland

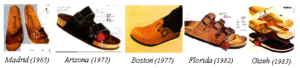

The following Birkenstock models were assessed by the District Court of Midden-Nederland:

The court held that the Madrid, Arizona, and Florida models meet the copyright work test. It identified seven characteristic design elements that, in combination, determine the original character:

- The flat bottom and the outline of the sole (“Umriss”) with straight, tapering side lines towards the front of the sandal;

- The unlined side of the sandal, leaving the cork visible;

- The shape of the footbed with a depression at the heel, a raised section in the middle on the inner side, and a toe grip consisting of a shaped ridge at the toes resembling an inverted square bracket;

- The downward-sloping walls (raised edges) running from back to front around the footbed;

- The (fastening) strap that runs along both sides of the sandal to the plastic sole and disappears between the footbed and the sole;

- Where the upper consists of multiple straps (Arizona/Florida), those straps (two or three) are cut from one piece of leather, causing them to meet at the sides and form a single whole before disappearing between the footbed and the sole;

- The fastening straps are not finished with visible stitching or other decorative elements.

The court rejected the argument that these elements are purely functional. The anatomical footbed, although inspired by a footprint, results from creative choices. According to the court, there is a wide variety of possible footprints, and therefore ample design freedom. The flat sole with straight side lines also deviates deliberately from the curved lines common in 1963 that follow the shape of the foot. Even the minimalist approach — omitting decoration and exposing the cork — is recognised as a conscious design choice rather than a cost-saving measure.

The court also dismissed the argument that the method of attaching the straps is purely dictated by the ago technique (a method in which the upper leather is stretched over a wooden or plastic last and glued to the sole), noting that various design options were still available within this manufacturing technique. For the Arizona and Florida models, the innovative choice to cut multiple straps from a single piece of leather is considered a distinguishing creative element.

Interestingly, the court deviates from the German BGH in just one sentence, without any substantive explanation: “The court reaches a different conclusion in this case.” This raises the question of whether such a brief departure from foreign case law contributes to the goal of European harmonisation of copyright.

Conclusion

The Birkenstock cases illustrate the tension between European harmonisation and national judicial autonomy. Although the factual application of the work concept is a matter for national law, one may question whether this “partial harmonisation” is sensible. After all, the aim of harmonisation is to create legal certainty and a level playing field within the internal market. When the same Birkenstock sandal is protected in the Netherlands but not in Germany, this aim seems unmet.

Moreover, commentators frequently observe (and criticise) that Dutch courts are relatively generous in granting copyright protection to utilitarian objects and, consequently, in issuing pan-European injunctions. This may encourage forum shopping within the EU.

Meanwhile, all eyes are on Luxembourg, awaiting the CJEU’s judgment in the joined cases MIO/Konektra, in which the European Court will hopefully provide further clarity on this long-disputed topic.

Read the whole judgment here.